In the decades following Singapore’s independence, the city-state confronted a succession of challenges with characteristic foresight and systematic planning, and the contemporary problem of e-waste computer recycling represents the latest chapter in this continuing narrative of adaptation. The computers that arrived in Singapore’s offices during the 1980s, bulky machines requiring dedicated air-conditioned rooms, have given way to generations of increasingly sophisticated and disposable technology. What distinguished Singapore then, as now, was not the absence of problems but the methodical approach to solving them before they became crises. The mounting accumulation of obsolete electronics demanded precisely this kind of anticipatory response.

The Historical Context of Technological Waste

Singapore’s relationship with waste management reveals a consistent pattern of intervention driven by geographical necessity. An island of limited land area cannot afford the luxury of careless disposal that larger nations might temporarily tolerate. When rapid industrialisation during the 1970s threatened to overwhelm rudimentary waste systems, the government responded with comprehensive planning: incineration plants to reduce volume, strict regulations on industrial discharge, public campaigns promoting cleanliness. Each measure reflected understanding that environmental degradation on a small island carries immediate consequences.

The emergence of electronic waste as a distinct category occurred gradually, then suddenly. Through the 1990s, computers remained expensive capital investments that organisations maintained for years. The turn of the millennium accelerated replacement cycles. Businesses adopted three-year refresh schedules. Consumers upgraded more frequently as prices fell and capabilities expanded. By 2010, the problem had acquired undeniable dimensions: tens of thousands of tonnes of electronic waste generated annually, much containing hazardous materials requiring specialised handling.

The Architecture of Singapore’s Response

The extended producer responsibility framework, implemented in phases beginning in 2021, represented characteristically Singaporean logic: those who profit from introducing products into the market bear responsibility for managing their end-of-life disposal. The scheme established clear obligations whilst providing flexibility in execution.

Key elements of the system include:

- Mandatory registration for producers and importers of electronic products, creating accountability for the full lifecycle of equipment they introduce to the market

- Financial contributions to support collection and recycling infrastructure, ensuring proper disposal capacity grows alongside product sales

- Designated collection points distributed across residential estates, commercial districts, and industrial zones for convenient public access

- Licensed recyclers meeting strict environmental and safety standards, preventing the informal processing that plagues waste management in less regulated environments

The network of collection points deserves particular attention. Strategising their placement required balancing accessibility against operational efficiency. Too few locations and participation suffers; too many and costs become prohibitive. The solution involved partnerships with retailers, community centres, and town councils, creating multiple pathways for responsible disposal.

The Process of Material Recovery

What occurs after collection reveals the sophisticated nature of modern e-waste computer recycling. At authorised facilities, incoming computers undergo systematic assessment. Equipment retaining functional value enters refurbishment programmes, extending useful life whilst providing affordable technology to schools, charities, and lower-income households. Devices beyond economical repair proceed to dismantling.

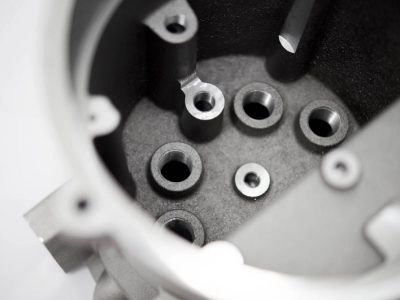

The dismantling process follows careful sequences:

- Removal of batteries and power supplies, which require separate handling due to fire risks and toxic contents

- Extraction of hard drives for certified data destruction, addressing security concerns that prevent many organisations from recycling equipment

- Separation of circuit boards containing precious metals and hazardous substances requiring specialised processing

- Recovery of bulk materials including aluminium casings, copper wiring, and steel components entering standard metal recycling streams

- Sorting of plastics by polymer type using optical identification technology, enabling high-quality recycling rather than downcycling or disposal

The efficiency of material recovery has improved markedly. Modern facilities achieve recovery rates exceeding 90 per cent by weight, with precious metal recovery from circuit boards approaching 95 per cent for gold and silver.

Environmental and Economic Imperatives

Singapore’s commitment to e-waste computer recycling serves dual purposes, environmental and economic, that reinforce rather than contradict each other. The environmental case requires little elaboration: preventing heavy metal contamination of limited land and water resources, reducing energy consumption through secondary material production, avoiding the greenhouse gas emissions associated with primary resource extraction.

The economic logic proves equally compelling for a nation importing virtually all raw materials. Each tonne of recovered copper represents copper that need not arrive by ship from Chile or Zambia. Each kilogramme of recycled aluminium reduces dependence on bauxite imports. The rare earth elements extracted from hard drives, though present in small quantities, carry disproportionate value given supply constraints and geopolitical considerations affecting primary sources.

Local employment in the recycling sector contributes additional economic benefit. Collection, logistics, processing, and administration create jobs requiring various skill levels, from manual sorting to engineering positions optimising recovery processes.

Lessons in Systematic Management

The effectiveness of Singapore’s approach derives from characteristics visible throughout the nation’s governance: clear regulatory frameworks, consistent enforcement, investment in necessary infrastructure, and public education explaining both benefits and procedures. These elements combine to create systems where desired behaviour becomes the path of least resistance rather than an obstacle course requiring unusual dedication.

The challenge of technological waste will intensify as device proliferation continues and replacement cycles potentially shorten further. Singapore’s methodical response demonstrates how systematic planning, supported by appropriate regulation and infrastructure, can manage problems that elsewhere accumulate into crises through inattention or the comforting assumption that solutions will emerge spontaneously.

Comments